A few months ago I sent out another survey to various people I know, centred on this optical illusion:

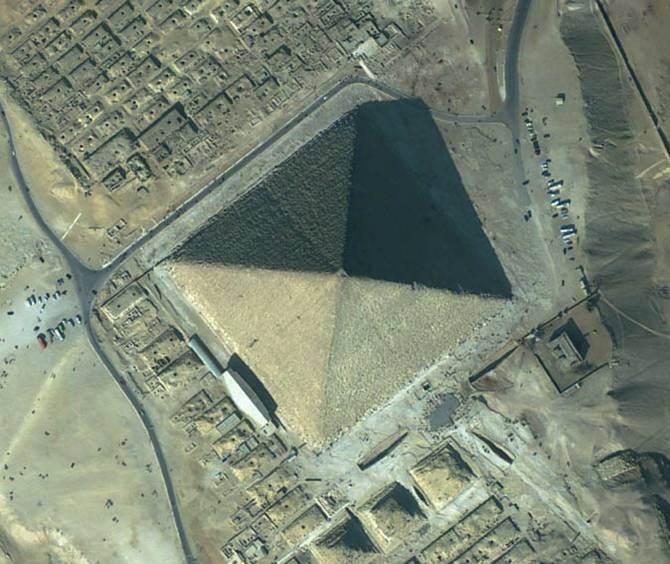

This is a rendering of a mask rotating about an axis, but because of the shadows and the precise orientation of the image, once it has turned fully away from you and you can see the inside hollowed out part of the mask, those hollows seem to “pop” out at you. Much in the same way that looking at a pyramid from the top looks like how that same pyramid would look from the bottom, but dug into the ground.

Except some people don’t see this illusion.

Background

I read about this phenomenon in an article by Scott Alexander. He surveyed a bunch of people and found that schizophrenic, autistic, and transgender people all reported weaker reactions to this illusion.

I recommend reading his article for more information about this as he is a practiced psychiatrist and I am a high school student who has never even taken a psychology class, but…

Basically, the theory as to why this happens is about the ways that these people’s brains work differently. One of the predominant theories in how human brains work in general is through a process in which our prior expectations of how things should be are combined with the actual raw sensory data that is available to us. This makes sense; the sensory data we have is noisy and unrefined, and it would be impossible for us to function using it alone. So we combine that information with what we expect to be the case, and it all gets smoothed out into the seemingly clear pictures we have of our surroundings.

An example is the image below. If you haven’t seen it before, it most likely looks like a bunch of random splotches…

…

…

…

…until I tell you that it’s an image of a cow, and then the image should snap into place. Situations like this usually don’t happen in real life because we only see cows when we’re at farms or petting zoos, or perhaps roaming the streets of India. In these cases we expect to see cows and everything works normally.

Where do our prior expectations come from? It seems that when our priors conflict with what our sensory data tells us, we slowly update to have different prior expectations. As babies we don’t know anything and have random models in our brain about what will happen, but as we grow older and gain more experience with the world we become better and better at predicting things.

So what does this have to do with autism / schizophrenia / transgender-ism (transgender-ia?)? (you think that “?)?” looks unappealing? I suppose a second parenthetical just makes it worse. But at least your pains have been acknowledged. Should acknowledgement of pain be valued more than its actual alleviation? What if the acknowledgement deepens the pain? For example, as is relevant to this article, may a diagnosis with autism set someone up for failure if they believe themselves constrained by their diagnosis? “Defined by their disability”? But today we cannot live with not knowing, everything needs a justification, everything needs a reason.)

Well, the (very tentative) idea is that these neurodivergences are related to differing strengths of prior expectations and sensory data in the brain. Specifically, these people’s prior expectations don’t play as big a role in their perception of the world. In schizophrenic people this leads to them putting a bunch of focus on random insignificant bits of sensory data; in autistic people lots of sensory data can be very overwhelming, probably because their brains put too much attention on it. I don’t totally understand this all, but you can read more here.

With transgender people the relationship seems less certain. But, trans people often dissociate, meaning that they sort of feel disconnected from their bodies. Which makes sense, if you identify as a different gender from the one you were assigned at birth. And there is a strong correlation between dissociation and weakened NMDA receptors, which are the receptors that have all of our “prior expectations” in them.

Ketamine is a drug that weakens NMDA function, and it also helps alleviate the symptoms of schizophrenia. So that further seems to suggest a relationship.

When it comes to the mask, the face pops out at us because of our priors. Faces are almost always facing out at us; we never see faces from the inside. So when the mask turns around, our priors are so strong that we just want to see it the other way. We expect the mask to be facing towards us, so it pops out as if it is.

I also think this elucidates something about how these priors work. It’s not like “oh since you saw the mask rotating that way your expectation is that it’s facing the opposite direction.” That’s not how priors work. Your priors are built up slowly over time, they’re not affected by high-level thoughts like these.

But for autistic / schizophrenic / transgender people, the priors aren’t that strong. So, in Scott Alexander’s survey, he found that they didn’t see the illusion as much. Now what did I find?

Results

The big problem for me is just not having enough responses; I had 41 in total, and I threw out one of them because the data would be annoying to analyse if I included it. If you did respond, thank you very much for the help. But, particularly in a situation where I am focusing on a few classes of people who make up a very small subset of the population, you really need more than that. At least in my previous study everyone’s response was equally meaningful. But here’s what I found.

With people who were diagnosed with autism, there is a small but significant correlation with reporting either a weak reaction or no reaction to the illusion. If I did my math right (which shouldn’t necessarily be assumed because I don’t really know anything about statistics) the p-value is 0.03 and the effect size is… 0.12. So there seems to be a correlation, just a weak one.

Or you could see that 33% of people who were diagnosed with autism didn’t see the illusion, while only 24% of non-autistic people reported weak or no reactions. While this might seem somewhat compelling, if you look further you will realise that that very suspicious “33%” figure comes from the fact that.. only three people diagnosed with autism took my survey.

What about schizophrenia? The numbers suggest there is a real correlation here! p = 0.0096 and effect size of 0.3. There is a significant, moderate, correlation. But, like last time, if we dive deeper into the data we see that.. only two schizophrenic people took my survey! Not enough to say anything for real.

We’re in a similar situation if we look at transgender women. p = 0.0017 and an effect size of 0.63. Wow! There definitely seems to be a correlation here, right? But wait, this data is coming from…. ONE TRANS WOMAN.

Analysis

The interesting thing about this situation is that the evidence does sorta line up with our hypothesis. Like, we do kinda see a correlation between autism, schizophrenia, and the illusion, however slight.

“Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.” That’s a quote from Carl Sagan, and it’s what I think about when looking at this situation.

Our hypothesis, our “claim” was that the viewing of this illusion relates to all these various mental conditions. This claim says that that the one autistic person, the one schizophrenic person, and the one transgender woman who failed to see the illusion did so because they all have weakened NMDA receptors.

But there’s a competing claim, which says that there’s no relationship at all. And this claim says that these people just randomly happened to fail the see the illusion. Or maybe they misinterpreted the question. Or maybe they’re trolling me and they just tried to click the wackiest options possible.

Just because your hypothesis lines up with the evidence you’ve found doesn’t make it true! There are always going to be lots of hypotheses that predict what you saw, but only one of them can be right.

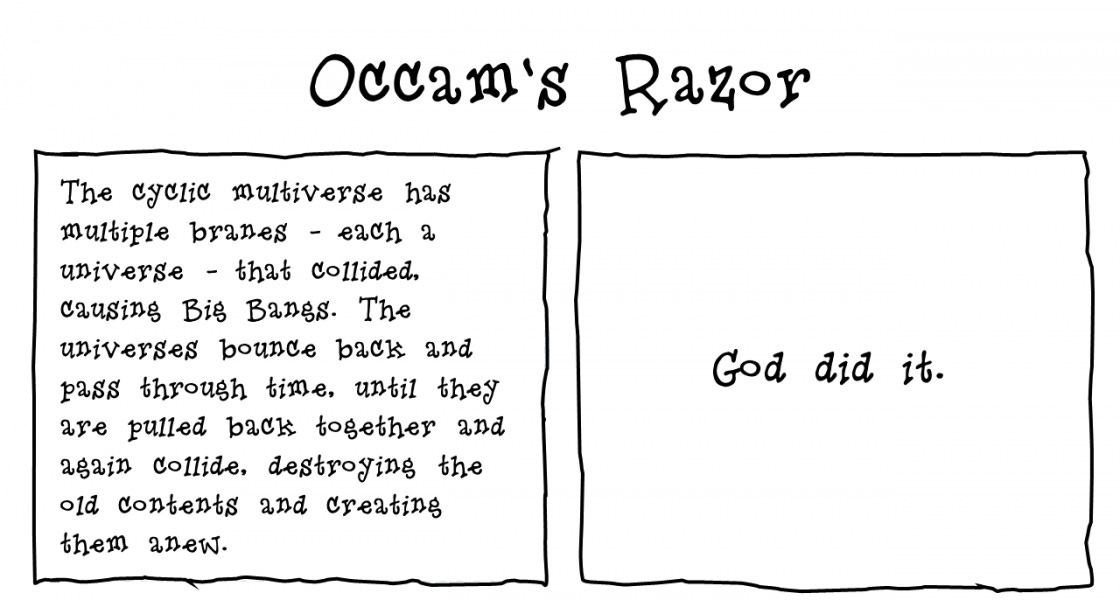

Occam’s razor tells us that the simplest possible explanation is usually the best one. To really make our extraordinary claim stand out from the ordinary ones, we need some extraordinary evidence. And we didn’t get that. We got some mediocre evidence that didn’t disprove the theory but didn’t really prove it either.

I hope you read the caption on that image or I’ll be very embarrassed.

There’s another problem, which is that the results I gave you were somewhat cherrypicked. For example, I didn’t really find a correlation between autism and not-seeing-the-illusion if I allowed self-diagnosed people into the bin of autistics. And while I found a correlation with trans women, there wasn’t really one for trans men.

This is what Scott Alexander calls the Elderly Hispanic Women Effect. You’re testing a drug, and it doesn’t really seem to be that useful overall, but if you run the statistics for… (checks every possible combination of traits possible) …Elderly Hispanic Women, it actually IS effective! Looks like we should start giving this drug to all the Elderly Hispanic Women, right??

So yeah, maybe the hypothesis is wrong.

But…

The original survey’s data still stands. With only 40 responses, anything that my data showed would be basically invalidated by Scott’s 5000.

In addition, before sending out this survey to people, I asked a few of my friends. Two of them were cisgender and they both saw the illusion. The other two of them were transgender and neither of them saw it! I know that’s just anecdotal evidence and not really meaningful, but still.

Other Stuff

I decided to look at the rest of my data to see if I could find anything else interesting. For example, the correlation between autism and being transgender has been widely reported on. Let’s see if our data has that:

p<0.05 and effect sizes of around 1, regardless of if I require the autism to be diagnosed or not! No more of the wishy-washiness from earlier. There is definitely a real, strong correlation.

I also asked people if they dissociated or not. Let’s see if I can find any relationships there.

For autism, there seems to be a good correlation. p=0.0014 and an effect size of 0.4.

There’s also a correlation between dissociating and being transgender. Note that in the dissociation question I provided “Yes, No, or Maybe” as possible answers. This relationship stood out the most only if allowing for both Yes and Maybe as answers. p=0.0002 and effect size of 0.4.

Also, 65% of total respondents said “Yes” or “Maybe”. Crazy! It’s because I have so many high schoolers in my data and we’re all really messed up 😔.

Here is the raw data if you’re interested.

P.S. I know I use too many exclamation marks! I just get so excited about this stuff! And they’re also nice because they can be used to convey irony. Aren’t they so cool ?!?!?!?!?!!?!!?!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Also, please tell me if you have criticisms on my writing. I didn’t edit this a ton so maybe there’s some silly errors. But also if you think it’s too dense or boring or something. I tried to pack a lot of information in a very tight package and I worry that not everything I hoped to communicate actually has been communicated. I just have so little experience writing stuff like this so I don’t know what works and what doesn’t.

nice 🙌